Altruism Versus Self-Interest

I’m quite a cynical person. I guess this cynicism comes from both my personal and professional experiences over the last ten years. That said, I’m also a realist, and quite the optimist when it comes to looking at the ‘big picture‘.

I work in digital marketing, and one of the biggest growth areas over the last 2 years has been Social Media. Friends, friends of friends, colleagues and family all post on Facebook, Twitter and other platforms about what they’re doing, what they’re reading, taking pictures of, watching, poking, tagging, pinning, and who and what they’re doing those things with. Suddenly everyone has become famous in their own right, and attention and intrigue into others lives are the drugs that keeps us hooked.

|

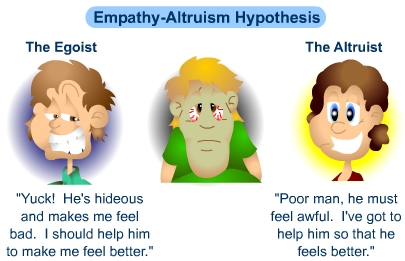

| Image from S-cool.co.uk |

Here’s my puzzle. Combine my human behaviour intrigue, cynicism, and realism and apply it to Social Media and everyday life. Do people make certain public posts, decisions and/or actions because they are truly altruistic, or are they doing it simply to feel better about themselves or look good in front of others and grab another 15 minutes of fame?

I’ve said in a previous post that I believe humans are (generally) inherently good by nature, but I think our online egos and interactions are beginning to turn the tables on what we believe is truly important.

I could delve deep into my thoughts and spend a week writing about what I think the answer is, but instead I’m going to copy an excerpt from chapter three of SuperFreakonomics, and let you decide for yourselves.

What do you think? Are we being manipulated by the powerful, intrusive world we currently live in?

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!